You bought the boat, you bought the safety gear, you booked a Powerboat Level 2 course but berthing’s still a challenge – what can you do to make it all a bit easier and more relaxing?

You certainly aren’t alone if you occasionally, or regularly, find getting your boat alongside a pontoon or into a finger berth challenging. Ask any instructor or commercial skipper and they have bad days and moments too – often more frequently than they’d care to admit!

Understanding a boat’s ‘happy position’

So what can you do to make it all a bit easier? To be able to handle your boat well you need to combine an understanding of how your boat will react to the conditions you are in, how to work with and manage the way the boat reacts and have the confidence to do so. Confidence in marina situations is like many things in life – it comes from knowledge and practice.

Let’s start by looking at how your boat reacts to the elements – wind and tide. Really key in being able to handle you boat well in a ‘close quarter’ situation is being able to predict what your boat does depending on the direction of the wind relative to the boat’s orientation.

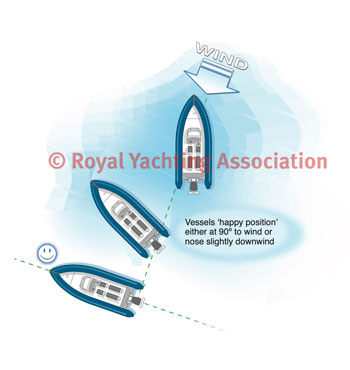

The great thing is that all powerboats react very predictably to the wind – the question is how! The first key principle is that powerboats are only ‘happy’ when they are lying side on to the wind. Whether you start with your bow pointing into the wind or the stern is facing the wind then the boat will ALWAYS rotate to lie side on to the wind.

What differs between different models/layouts of powerboats is the speed at which they rotate to this ‘happy’ position. Four berth family cruisers with high topsides and lots of canvas typically have very light bows and heavy sterns. They tend to rotate very rapidly and actually often do so as quickly from stern to wind as they do from bow to wind.

So what can you do about this tendency to want to rotate to lie beam onto the wind? By knowing what your angle is relative to the wind you can predict what will happen and so use boat handling skills to keep control of the bow or it may be you are happy to let the bow get taken if there is space for it to do so. By being aware of what will happen and being able to let it happen or work with it immediately makes life more relaxing and sets you up better in the marina.

So what about tide or stream? When looking to understand how the tide or stream will affect your boat the mistake I often see is people looking to see what the tidal height is and is it rising or falling. This is the wrong thing to look for as what really matters is how the water is flowing where you boat is and therefore what direction the boat will be pushed in. The tide moves the whole body of water around the boat and in itself doesn’t rotate the boat but if the tide is flowing around objects or over an uneven seabed the disturbed water might create less predictable movements. The key is to watch the water and see how it is moving so you can factor this into your planning stage.

Before any maneuver you also need to be aware of what depth of water you have around you and what other boats are doing where you are maneuvering.

This gathering of data – wind, tide/stream, depth and other craft – is the ‘Assessment’ phase. Assess well and the next stage – ‘Planning’ will go a whole lot better.

Practising your skills

The planning element marries an understanding of how your boat handles (is it one or two engines, does it have a bow thruster, how quickly does it get pushed around by the wind) to the specifics of the berthing situation you are facing.

So what exercises can you do to develop this understanding and so make handling your boat and planning maneuvers easier?

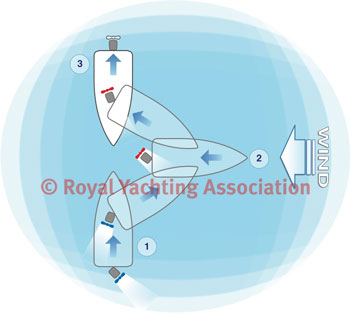

Exercise 1: Find a clear patch of water. Head directly into wind. Stop. Once the boat has stopped moving how quickly does it rotate to its ‘happy’ place? Does it rotate at a constant speed, how quick is it, how much does it vary at different wind speeds. Sometimes you’ll find the bow rotates so fast it ‘overshoots’ this side on position but then the bow will rotate back to the happy position as it settles.

Exercise 2: Do the same but with the stern into the wind. Try it with and without the canvass up as this can make a big difference to the speed of rotation especially if wind fills the enclosed cockpit area through an open section at the stern.

Exercise 3: Find a large open area of water to practice holding the bow into the wind. Position bow to wind. Watch the bow, which way is it starting to move? If to the left/port turn hard to the right and into/out of gear (half second movements) to stop the boat rotating – we call this ‘steer then gear’. Centre the helm, go again. Try to hold the bow for a few minutes without losing it.

Exercise 4: Repeat but stern to wind.

Exercise 5: If there is any tide/stream find a position where you look to your right or left at an object and ‘stem the tide’ to hold position relative to the object. Try ‘ferry gliding’. Angle the bow slightly left and work against the tide to crab sideways whilst still keeping the object directly to your side.

Exercise 6: Put the practice from all of these exercises together by finding a mooring buoy with a bit of space around it and hopefully some wind and tide/stream and try and position the boat two boat lengths away. Hold for one minute. Halve the distance, hold for one minute. Halve the distance etc. Keep getting closer until you are happy holding the boat against the wind and tide/stream a metre or so away for any length of time.

If you get out and learn about your boat using these exercises I guarantee you’ll start to feel happier in close quarter situations.

Marina berths

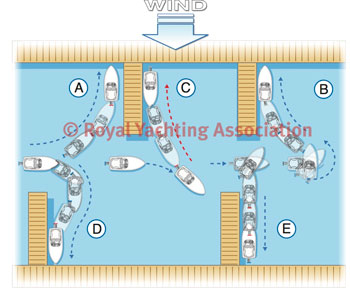

Let’s look at a few marina berths to assess the issues we are likely to face when approaching some berths and so create a plan of approach that will (hopefully!) work.

Berth A: As we established, our powerboats are only ‘happy’ when they are side (‘beam’) on to the wind. We also determined that with many powerboats with light bows and heavy sterns the bow can be very quick to rotate from pointing into the wind to lying side on. Therefore, with Berth A we need to keep a careful watch on the bow as when we approach the berth bow into wind the bow naturally wants to rotate either towards the pontoon or to the left where another boat may be berthed. Our approach from the left-hand side of the marina also means the berth is ‘open faced’ and so fully visible to us. Approaching from this angle allows us to carry momentum onto the berth but we need to be careful though not to overdo things. As we approach ‘A’ we need to time our turn and come to a stop so we are not sliding sideways past the berth. Knowing when to turn is a matter of learning your boat and lots of practice. In summary: Slow down, time the turn, get a nice angle onto the pontoon, control the bow.

Berth B: It is obviously very similar to A but from our approach direction the berth is ‘closed face’ to us. There is no absolute right or wrong way to approach but a good way is to go just past, turn to get a good angle of approach and enter the berth. The rest of the things to think about are the same as for A.

Berth C: Can be a straightforward berth to get into if you set yourself up right. Powerboats generally don’t need much effort to keep them holding ‘stern to wind’. Therefore, so as long as you turn at the right time you can gently ease yourself stern first into the berth. As you approach the berth I would tend to stay slightly to the left of the channel (the ‘upwind’ side) to give yourself some room for the turn and ensure that you are not blown side on down onto the boats to your right – the ‘danger side’. The image shows a small turn initially to the right then reverse into wind but it can work just as well without that turn to the right but with an initial turn to the left (port) and reverse to start the turn and arrest forward movement in one move. Try both and see what you think.

Heading into Berth D at first glance may seem simple as the wind is behind you but there is a need to be careful for a few reasons. In the example shown the powerboat heads straight into the berth. Another option is to go past the berth, turn and the berth becomes ‘open faced’. Be careful on the turn though as if you get side on you may get blown on to the other boats quickly, also its easy to head into the berth too fast so get into position with the stern into the wind and ease in slowly.

Berth E can be a tricky berth. The problem with this berth is the need to hold the bow into the wind as you reverse into the berth. As we have already established the wind wants to push the bow off to the left or right so we need to juggle reversing in, the wind potentially increasing our momentum and keeping the bow under control. This is precisely where a bowthruster is worth its weight in gold. With or without a thruster there is a need to fender well before approach and time your turn so that you don’t have to reverse too far towards the berth.

Remember with any of these berths a good skipper knows when to pull the plug and abort. For E it may be bows in first makes more sense or perhaps speaking to the marina and going alongside in a really simple berth and moving the boat when the wind eases. Whatever you decide to do remember two things 1) there is no shame in deciding to not approach a berth in the conditions you face 2)the boat is only plastic and can be repaired – keep hands and legs clear. Only use fenders to fend off.

With any approach and berth consider following this process: Assess the wind, tide, depth and impact of other vessels Plan the approach factoring in this assessment Execute the approach but ensure that you have an escape route planned in too.

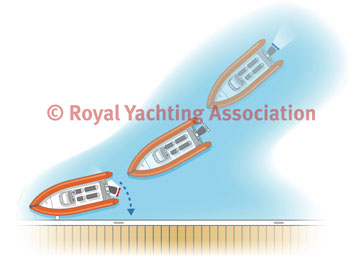

As we have said many many times you won’t get good at this without practice. Start with loads of turns through 180 degrees, then find a long straight pontoon and loads of practice coming really well alongside at a set location.

Then progress to finger berths, find a double one free of other boats and pretend there is a boat in the other berth. Go into it again and again so that it becomes easier, then find another berth and go again. Start by doing this with no wind, then with a little bit, then with a bit more. If needs be get a good instructor out with you to hone those skills. Remember things will go wrong from time to time – don’t power out of a problem and if you are going to ‘crash’ do it slowly, finally not every coming alongside will be ‘pretty’ – just make sure its safe. Have fun afloat!

Tip Bowthrusters – they’re cheating aren’t they? Let’s nail this one – no they aren’t and any old salty seadog that tells you otherwise needs to get real. The thing about bowthrusters is to use them in the right way. The bowthruster should be used as a means to tidy things up not to achieve the objective. For example, let’s say you are turning through 180 degrees to return back in the opposite direction. Aim to achieve the turn using engines and steering and add the bowthruster in to tidy up the turn if needed. What you don’t want to be doing is using the bowthruster to fully turn the bow as that risks overloading a system drawing a high current and risks the bowthruster ‘tripping’ just when you really need it. If you struggle to do the turn without the use of a thruster then its well worth a few hours with an instructor to develop the skills to do the turn without relying on the thruster.

This article was adapted from an article originally written by Powerboat Training UK for Powerboat & RIB Magazine and published in 2019. The article is based on the relevant sections from the RYA Powerboat Handbook.

The RYA Powerboat Handbook is available from the RYA Shop either as a paperback or as an eBook.